Louisa Chase: 1985 - 1990

By the mid-1980s, Louisa Chase’s compositions became increasingly abstract in an attempt to depart from symbolist figuration. She revealed in an interview with Arts magazine in 1989 that “...the old images could not hold anymore. [I] needed to find a new language.”

By the mid-1980s, Louisa Chase’s compositions became increasingly abstract in an attempt to depart from symbolist figuration. She revealed in an interview with Arts magazine in 1989 that “...the old images could not hold anymore. [I] needed to find a new language.”

Fiercely independent and relentless in her quest to further define her voice as an artist, she forced herself to give up nearly everything to find a way to create

a new kind of painting based on the physicality of the gesture and exploration of abstraction.

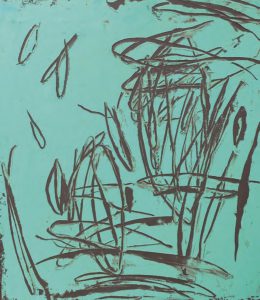

Chase stopped illustrating her ideas and experimented with more aggressive drawing and mark-making on small canvases in a simplified color palette. Excavating the canvas as if carving into a woodcut, Chase incised into the surface of a fresh layer of paint to reveal what lay dormant beneath. Scraping into layers of contrasting colors, she pushed her marks with a sense of urgency to capture life’s energy, reminiscent of Alberto Giacometti’s work, rather than merely describing its forms. Only then, the basic shape of heads and figures emerged to give a sense of space. In the same vein, she incorporated text as image by employing automatic writing as a more direct line of communication, reflected in her lithographs Mountains and Spooks and in her pivotal painting No Where, Now Here from 1986-87.

In 1987, Louisa Chase took a two-month trip to Greece to visit friend and fellow artist Brice Marden on the island of Hydra. In an “ah-ha” moment, the influence of the light and landscape and inspiration from Marden’s paintings on marble found on the island, inspired her to develop a new visual language.

She restricted her work to the pictorial codes of drawing and geometry, recalling, “I had to rid myself of everything, literally going back to scribbling and playing with blocks.” Her new visual language personified the

duality of chaos and order: the contrast of a simple geometric foundation existing within a gestural field of marks and lines. Although the elements are simple, the results are deeply complex.

Similar to her game pieces of the late-1970s, geometric elements offered some semblance of a structured language within a secondary language of gestural marks. Reminiscent of Dutch modernist Piet Mondrian’s blocks of primary colors of red, yellow and blue, Chase’s geometric color blocks are the “knowns” or “constants” engulfed in the “play of the game”—stacked in different configurations to symbolize figures, boats and houses.

Chase had discovered a new way of drawing—a nuanced and expressive line created in a reductive manner by scraping, smearing, and carving through multiple painted layers to unearth what lies beneath. This technique revealed lyrical, nuanced marks floating in and out of a luminous and pristine surface of white encaustic paint, which evoked the light and textures of Grecian marble and white-washed architecture. The mark-making, or “scribbling” as the artist labeled it, serves to indicate and inscribe Chase’s presence in the work. The marks are soulful, articulate and calligraphic, resonating throughout the picture plane. She no longer relied on the symbolic image of the “hand” to establish her presence within her work.

The build up and decomposition of layers of these marks juxtaposed with geometric forms remained a constant focal point in her prints and paintings throughout the 1990s. She had developed a rational language within an emotional landscape that physically captured an internal state of being that was in flux but produced a balanced and harmonious composition.