In The Land of War Canoes: The Impact and Influence of Edward Curtis' Silent Film on Contemporary Native American Art and Artists

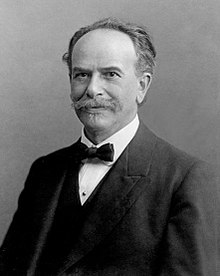

Edward Sheriff Curtis (February 19, 1868 - October 19, 1952) was an American photographer and self-taught and appointed ethnologist whose work focused on the American West and Native American people. In the early 1900s, Curtis was commissioned to produce a photographic series on Native Americans of the United States and Canada by J.P. Morgan. Over the course of twenty years, Curtis made over 10,000 wax cylinder recordings of Native American language and music, took over 40,000 photographs of members of over 80 different tribes, and created a singular silent film In The Land of Headhunters. This work, done in the spirit of salvage anthropology, was intended by Curtis to depict the vanishing Native American way of life. Debuting in 1914. Since then, the film has served as a flashpoint for discussing Native rights, self-definition and more. But today, we can discuss how this film, renamed in 1967 at In The Land of The War Canoes, has helped to perpetuate artistic traditions for Indigenous peoples, particularly for the Kwakwaka'wakw whom the film depicts, and explore the connections between the making of this film and a work on view at the Leepa-Rattner Museum of Art.

In the 19th century, with increasing European and Euro-American colonization of North America, an increase in violence and racism towards Indigenous peoples, disease, and both United States and Canadian governmental actions including the forced removal of the Cherokee and other tribes via the Trail of Tears, the Native American populations throughout North America were in decline. Many Europeans and Euro-Americans saw the population decline coupled with the "disappearance of culture" through forced assimilation and crafted a concept of the "vanishing race". Because of this theory, Americans and Euro-Americans believed it was their responsibility to preserve cultural memory and traditions of Indigenous peoples through the collecting of photographs and ethnographic and anthropological objects in a practice known as "salvage anthropology" or "salvage ethnology".

The most prominent scholar operating within this practice was Franz Boas (July 9, 1858 – December 21, 1942), a German-American anthropologist considered to be "the father of American anthropology". Boas first began collecting for the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition or Chicago World's Fair, the 400th anniversary of explorer Christopher Columbus' arrival in the Americas. For the Exposition, Boas, working for the Peabody Museum at Harvard University, was to create anthropological and ethnographic exhibits on the Indigenous Peoples of the Americas. The exhibits were created to depict late-nineteenth century Native American and First Nations peoples "in their natural conditions of life" to provide a contrast with and celebrate Western accomplishments in colonization. After the Exposition was over, the exhibits Boas had created formed the basis of the newly created Field Museum in Chicago where he was appointed Curator of Anthropology.

The most prominent scholar operating within this practice was Franz Boas (July 9, 1858 – December 21, 1942), a German-American anthropologist considered to be "the father of American anthropology". Boas first began collecting for the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition or Chicago World's Fair, the 400th anniversary of explorer Christopher Columbus' arrival in the Americas. For the Exposition, Boas, working for the Peabody Museum at Harvard University, was to create anthropological and ethnographic exhibits on the Indigenous Peoples of the Americas. The exhibits were created to depict late-nineteenth century Native American and First Nations peoples "in their natural conditions of life" to provide a contrast with and celebrate Western accomplishments in colonization. After the Exposition was over, the exhibits Boas had created formed the basis of the newly created Field Museum in Chicago where he was appointed Curator of Anthropology.

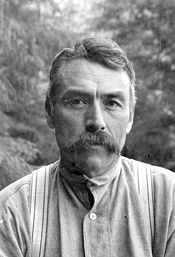

In 1896, Boas left the Field Museum and became the Assistant Curator of Ethnology and Somatology at the American Museum of Natural History. It was under their employment that, in the following year, he organized the Jesup North Pacific Expedition, a five-year-long field-study of the peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast. Throughout the expedition, Boas and his associates employed Indigenous peoples as interpreters and guides. One such individual employed by Boas in the Jesup Expedition was George Hunt.

George Hunt (February 14, 1854 – 1933) was the son of a Hudson's Bay Company official and a Tlingit noblewoman. He was raised in Fort Rupert and served as a consultant to Franz Boas throughout the Jesup Expedition and proved particularly useful when Boas made contact with the Kwakwaka'wakw.

George Hunt (February 14, 1854 – 1933) was the son of a Hudson's Bay Company official and a Tlingit noblewoman. He was raised in Fort Rupert and served as a consultant to Franz Boas throughout the Jesup Expedition and proved particularly useful when Boas made contact with the Kwakwaka'wakw.

The Kwakwaka'wakw live on northern Vancouver Island and on the mainland in the region of Queen Charlotte Sound and Johnstone Strait. Throughout the tribe. art played a major role in both everyday life and in ceremonial affairs, most notably in the Hamatsa Dance and in the Potlatch.

The Kwakwaka'wakw live on northern Vancouver Island and on the mainland in the region of Queen Charlotte Sound and Johnstone Strait. Throughout the tribe. art played a major role in both everyday life and in ceremonial affairs, most notably in the Hamatsa Dance and in the Potlatch.

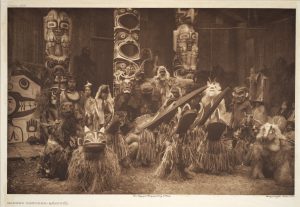

The Hamatsa, or cannibal dance, is an origin story adopted by the Kwakwaka'wakw but developed by the Haisla or Heiltsuk peoples. It recounts the experience of a group of hunters who, pursuing mountain goats, encounter the Bakbakwalanuxsiwe, the great man-eating spirit who lives in the north. At the invitation of a woman who offers to help the hunters enter the home when the spirit is out roaming the earth, the hunters dig a hole in the floor of the spirit's house, fill it with hot stones, and hide in the corner of the house to await the spirit's return. The monstrous Bakbakwalanuxsiwe, whose body was said to be completely covered in mouths, returns to his home dancing and surrounded by soaring birds. As the spirit dances with eyes focused upwards, he falls into the pit of hot stones dug by the hunters and dies. The hunters learn the songs of the cannibal spirit from the woman and the birds and return home to their village with masks and other ritual regalia to be displayed to their community. Descendants fo these hunters have the privilege and rights to perform the Hamatsa. When boys come of age within the Kwakwaka'wakw, they are initiated into the Hamatsa by being brought to a site outside the village. There, they are taught the sons, history, and dances of the ceremony. This is meant to reflect the voyage of the hunters to the house of the Bakbakwalanuxsiwe. There, the initiate is said to become possessed with cannibalistic cravings. When they return to the village, the initiate would lunge at ceremonial attendees, trying to bit them. Although the initiate's attendants would attempt to restrain him, sometimes he would escape their grip and actually appear to sink their teeth into a member of the audience. In actuality, the "victim" knew in advance this would occur, and was paid by the initiate's family. Accompanying the initiate would be dancers wearing carved and painted bird masks such as the ones seen in this still from Curtis' 1914 film, meant to embody the birds the circled the Bakbakwalanuxsiwe. These beaks were articulated and could be snapped during the dances, creating not only a visual but also an aural experience for the audience.

Potlatches were for the Kwakwaka'wakw, rather lavish affairs, often held to memorialize deceased ancestors or celebrate marriages, the erecting of houses and totem poles, or other celebratory events. The potlatch was a celebratory feast where the host, typically the leader, would distribute wealth or valuable items such as art objects in order to demonstrate their wealth and power. This ceremony reaffirmed the bonds of family, clan, tribe, and connections with the supernatural world. Additionally, the Kwakwaka'wakw and other Northwest Coast First Nations peoples used potlatches as a way to manage territories and resources. In addition to the feasting and gift-giving, potlatches involved music, dancing, storytelling, orations, and games. Throughout the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, Kwakwaka'wakw potlatches became more and more elaborate.

During the last decades of the nineteenth century, both the United States and Canadian official government policy towards aboriginal peoples was assimilation. The Northwest Coast people posed special problems to the assimilationists, because these hierarchically organized people with a keen sense of property devoted considerable time and effort to accruing wealth - not to save it, but to share it with their communities. Officials and missionaries both firmly believed that the potlatches which they judged to be senseless extravagances, had to be eradicated before Northwest Coast Native groups could be called civilized. As a result, in 1884, the Canadian Government banned the potlatch and related dances like the Hamatsa. So in other words, in addition to taking the Native lands, reducing their ability to maintain a subsistence economy, and endorsing racist attitudes, the government criminalized ceremonies central to identity and culture.

In 1892, when Boas and Hunt encountered the Kwakwaka'wakw, the potlatch ban had been in effect for nearly a decade. Despite the law, the Kwakwaka'wakw continued to potlatch. Because of this, they were considered "incorrigible" by the Canadian authorities. When officials began to enforce the anti-potlatch law, the Kwakwaka'wakw designed various subterfuges to avoid it. Sometimes they would hold potlatches in remote villages in the middle of winter, when police had difficulty traveling. Sometimes they would have potlatches on Christmas, insisting the host was merely giving away Christmas presents. And because they continued to potlatch, the Kwakwaka'wakw continued to need and produce art. In fact, although they had erected relatively few totem poles during the nineteenth century, in the first decade of the twentieth century poles began to proliferate, especially in Alert Bay, each one signifying an ostentatious disregard for Canadian law and a visual expression of Kwakwaka'wakw resistance to white authority.

In 1892, when Boas and Hunt encountered the Kwakwaka'wakw, the potlatch ban had been in effect for nearly a decade. Despite the law, the Kwakwaka'wakw continued to potlatch. Because of this, they were considered "incorrigible" by the Canadian authorities. When officials began to enforce the anti-potlatch law, the Kwakwaka'wakw designed various subterfuges to avoid it. Sometimes they would hold potlatches in remote villages in the middle of winter, when police had difficulty traveling. Sometimes they would have potlatches on Christmas, insisting the host was merely giving away Christmas presents. And because they continued to potlatch, the Kwakwaka'wakw continued to need and produce art. In fact, although they had erected relatively few totem poles during the nineteenth century, in the first decade of the twentieth century poles began to proliferate, especially in Alert Bay, each one signifying an ostentatious disregard for Canadian law and a visual expression of Kwakwaka'wakw resistance to white authority.

After the Jesup Expedition, George Hunt continued to collect Northwest Coast material for the American Museum of Natural History. He was, in 1902, most notably involved in the controversial acquisition of the Yuquot Whaling Shrine. He settled down with a Kwakwaka'wakw wife and started a family near Fort Rupert. Nearly a decade later, Hunt was to work with none other than Edward Curtis on his 1913 silent film In The Land of The Head Hunters, filmed in Alert Bay with the Kwakwaka'wakw.

An extension of their previous encounters with ethnographers and collectors, the film helped the Kwakwaka'wakw evade the potlatch ban, maintain their expressive culture, and emerge as actors on the world's stage. By adapting their traditional ceremonies for Curtis' film while refusing to play stereotypical "Indians", the Kwakwaka'wakw played a vital role in the development of the most modern of art forms - the motion picture. Like his photographs, Curtis' film was originally meant to capture a "vanishing race". Instead, when resituated within the history of motion pictures, and framed by current Kwakwaka'wakw perspectives, this film can be viewed as evidence of ongoing cultural survival and transformation under shifting historical conditions.

An extension of their previous encounters with ethnographers and collectors, the film helped the Kwakwaka'wakw evade the potlatch ban, maintain their expressive culture, and emerge as actors on the world's stage. By adapting their traditional ceremonies for Curtis' film while refusing to play stereotypical "Indians", the Kwakwaka'wakw played a vital role in the development of the most modern of art forms - the motion picture. Like his photographs, Curtis' film was originally meant to capture a "vanishing race". Instead, when resituated within the history of motion pictures, and framed by current Kwakwaka'wakw perspectives, this film can be viewed as evidence of ongoing cultural survival and transformation under shifting historical conditions.

The film combines many accurate representations of aspects of Kwakwaka'wakw culture, art, and technology from the era in which it was made with a melodramatic plot based on practices that either dated from long before first contact of the Kwakwaka'wakw with Euro-Americans or were entirely fictional. The artwork, ceremonial dances, clothing, architectural paintings, and even the construction of canoes reflect Kwakwaka'wakw culture with documentary accuracy. The most sensational elements of the film - the head hunting, sorcery, and handling of human remains - all reflect much earlier practices that had long been abandoned by the Kwakwaka'wakw. The whaling practices seen in the film? Not even remotely Kwakwaka'wakw! Rather, they were borrowed from neighboring First Nations peoples (and the whale rented) for purely dramatic and cinematic reasons.

The film produced some of the most unforgettable images of Kwakwaka'wakw ceremonial life. The scene with canoes approaching land, carrying three masked dancers - Wasp, Thunderbird and Bear - each dramatically waving their arms and swaying their bodies, has captured the imagination of the world for more than a century.

The film produced some of the most unforgettable images of Kwakwaka'wakw ceremonial life. The scene with canoes approaching land, carrying three masked dancers - Wasp, Thunderbird and Bear - each dramatically waving their arms and swaying their bodies, has captured the imagination of the world for more than a century.

In The Land of the Head Hunters was the first feature-length film whose cast was composed entirely of Native North Americans. The film premiered simultaneously at the Casino Theatre in New York and the Moore Theatre in Seattle on December 7, 1914. The film was accompanied by a score composed by John H. Braham, a musical theatre composer who had also worked with Gilbert and Sullivan. The film was met with critical acclaim, but made only $3,269.18 in its initial run. Soon after its release, the movie disappeared from the world of cinema and was forgotten. In the late 1940's a damaged copy was found in a dumpster and procured by a collector of old movies who donated it to the Field Museum in Chicago. In the 1960s, George Quimby, director of the Burke Museum at the University of Washington in Seattle collaborated with fellow curator, artist, and Northwest Coast Native art scholar Bill Holm to restore the film. Holm brought the film to the Kwakwaka'wakw in Fort Rupert, some whom were descendants of the actors, and worked with the contemporary Kwakwaka'wakw to make a soundtrack of speeches and songs. The film was released in 1967 under a new name, In The Land of the War Canoes and is now recognized as a classic in its genre. The film was selected in 1999 for preservation in the US National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, and aesthetically significant." Today the film can be viewed as a lens through which to reframe and re-imagine the changing terms of colonial representation, cultural memory, and intercultural encounter as well as a catalyst for modern and contemporary Kwakwaka'wakw art and artists.

One of the Kwakwaka'wakw artists who worked on Curtis' film creating carvings and paintings was Mungo Martin. Chief Mungo Martin (1879 - August 16, 1962) was an important figure in modern Northwest Coast art. Born in Fort Rupert to parents of the Kwakwaka'wakw Nation, he was son of Yaxnukwelas, a high-ranking man of Gilford Island. He participated as a young man in Curtis' film, creating large totem poles for the interior potlatching scenes. After the film was made, he continued to be a prolific artist.

One of the Kwakwaka'wakw artists who worked on Curtis' film creating carvings and paintings was Mungo Martin. Chief Mungo Martin (1879 - August 16, 1962) was an important figure in modern Northwest Coast art. Born in Fort Rupert to parents of the Kwakwaka'wakw Nation, he was son of Yaxnukwelas, a high-ranking man of Gilford Island. He participated as a young man in Curtis' film, creating large totem poles for the interior potlatching scenes. After the film was made, he continued to be a prolific artist.

In 1949, the University of British Columbia (UBC) purchased several old Kwakwaka'wakw poles, house posts, and an 11-piece house frame which they planned to erect outdoors on their campus. These pieces needed to be restored and repainted before they were put on view. And so the Museum of Anthropology, part of UBC, contacted Martin who had created one of the totem poles, a Raven-of-the-Sea pole from Alert Bay, in 1900. From 1949 to 1951, Martin was in residence at the Museum restoring the pieces. In 1951, the Museum erected these poles on a three-acre site on the UBC campus called Thunderbird Park and appointed Mungo Martin the park's Master Carver.

In 1949, the University of British Columbia (UBC) purchased several old Kwakwaka'wakw poles, house posts, and an 11-piece house frame which they planned to erect outdoors on their campus. These pieces needed to be restored and repainted before they were put on view. And so the Museum of Anthropology, part of UBC, contacted Martin who had created one of the totem poles, a Raven-of-the-Sea pole from Alert Bay, in 1900. From 1949 to 1951, Martin was in residence at the Museum restoring the pieces. In 1951, the Museum erected these poles on a three-acre site on the UBC campus called Thunderbird Park and appointed Mungo Martin the park's Master Carver.

In 1953, Martin built a Kwakwaka’wakw style house which he named “Wawaditla” which translates at “he orders them to come inside”, an expression of tremendous authority and power – meaning the chief is so powerful that he can command anyone to come into his house and serve him. It featured a vividly painted façade and interior house posts. Outside stood a totem pole. The painting on the façade is Martin’s version of a crest image owned by his ancestor who lived in Fort Rupert. The pole does not depict Martin’s own privileges but instead the crests of four Kwakwaka’wakw tribes. To validate this building, its imagery, and the exterior pole, Martin hosted a splendid three-day potlatch. Two years before, the potlatch prohibition had been eliminated from the Indian Act, and Martin’s opening ceremony for this house represented the first legal potlatch since 1884.

In 1953, Martin built a Kwakwaka’wakw style house which he named “Wawaditla” which translates at “he orders them to come inside”, an expression of tremendous authority and power – meaning the chief is so powerful that he can command anyone to come into his house and serve him. It featured a vividly painted façade and interior house posts. Outside stood a totem pole. The painting on the façade is Martin’s version of a crest image owned by his ancestor who lived in Fort Rupert. The pole does not depict Martin’s own privileges but instead the crests of four Kwakwaka’wakw tribes. To validate this building, its imagery, and the exterior pole, Martin hosted a splendid three-day potlatch. Two years before, the potlatch prohibition had been eliminated from the Indian Act, and Martin’s opening ceremony for this house represented the first legal potlatch since 1884.

On October 16, 1923 in the Kwakwaka'wakw community of Fort Rupert, Henry Hunt was born, the grandson of Curtis' collaborator, ethnologist George Hunt. In 1939, Henry Hunt (October 16, 1923 - March 13, 1985) married Helen Martin, the adopted daughter of Kwakwaka'wakw artist Mungo Martin. Henry worked as a logger and fisherman and took up wood carving after the marriage. In 1954, Hunt went to work for his father-in-law as Martin's chief assistant at Thunderbird Park where he studied traditional wood carving and worked in the Museum's collections, helping to restore and preserve Aboriginal art. When Mungo Martin died in 1962, Hunt succeeded him as Thunderbird Park's Master Carver. Hunt remained at the museum for over twenty years until he retired in 1974.

On October 16, 1923 in the Kwakwaka'wakw community of Fort Rupert, Henry Hunt was born, the grandson of Curtis' collaborator, ethnologist George Hunt. In 1939, Henry Hunt (October 16, 1923 - March 13, 1985) married Helen Martin, the adopted daughter of Kwakwaka'wakw artist Mungo Martin. Henry worked as a logger and fisherman and took up wood carving after the marriage. In 1954, Hunt went to work for his father-in-law as Martin's chief assistant at Thunderbird Park where he studied traditional wood carving and worked in the Museum's collections, helping to restore and preserve Aboriginal art. When Mungo Martin died in 1962, Hunt succeeded him as Thunderbird Park's Master Carver. Hunt remained at the museum for over twenty years until he retired in 1974.

Henry Hunt and Helen Martin had six sons and each were trained in the art of Kwakwaka'wakw carving. Three of Henry's sons - Tony, Stanley and Richard - went on to establish their own careers as artists.

Tony Hunt, Sr. (August 24, 1942 - December 15, 2017), the first-born son of Henry and Helen, was born in 1942 in the Kwakwaka'wakw community of Alert Bay. As a child, he learned how to carve alongside his father under the tutelage of his grandfather Mungo Martin. When Mungo Martin died in 1962 and Tony's father, Henry Hunt became Master Carver at Thunderbird Park, Tony became his assistant. He worked at the park until 1970 when he opened The Arts of the Raven Gallery in Victoria.

Tony Hunt, Sr. (August 24, 1942 - December 15, 2017), the first-born son of Henry and Helen, was born in 1942 in the Kwakwaka'wakw community of Alert Bay. As a child, he learned how to carve alongside his father under the tutelage of his grandfather Mungo Martin. When Mungo Martin died in 1962 and Tony's father, Henry Hunt became Master Carver at Thunderbird Park, Tony became his assistant. He worked at the park until 1970 when he opened The Arts of the Raven Gallery in Victoria.

In 1984, Kraft Foods, Inc. commissioned Tony Hunt, Sr. to carve a replacement totem pole for a Kwakwaka'wakw pole that had been donated by James L. Kraft to the city of Chicago in 1929. Installed at the waterfront of Lake Michigan, after decades in the park, the pole had suffered greatly from weather deterioration as well as vandalism. Tony Hunt, Sr. worked to carve a new pole, a Kwanusila (Thunderbird) pole. The original pole was sent to the Museum in British Columbia for preservation and study as its historical and artistic value was considerable. Today, when visiting Lakeside Park, you can view Tony Hunt Sr.'s pole. His work is also held by the St. Louis Art Museum, the Fine Art Museum of San Francisco, the Field Museum in Chicago and is in the collections of many private owners. His grand masterpiece is considered to be the Fort Rupert Big House, or ceremonial house, which is the largest traditional native structure ever built in the Pacific Northwest.

In 1984, Kraft Foods, Inc. commissioned Tony Hunt, Sr. to carve a replacement totem pole for a Kwakwaka'wakw pole that had been donated by James L. Kraft to the city of Chicago in 1929. Installed at the waterfront of Lake Michigan, after decades in the park, the pole had suffered greatly from weather deterioration as well as vandalism. Tony Hunt, Sr. worked to carve a new pole, a Kwanusila (Thunderbird) pole. The original pole was sent to the Museum in British Columbia for preservation and study as its historical and artistic value was considerable. Today, when visiting Lakeside Park, you can view Tony Hunt Sr.'s pole. His work is also held by the St. Louis Art Museum, the Fine Art Museum of San Francisco, the Field Museum in Chicago and is in the collections of many private owners. His grand masterpiece is considered to be the Fort Rupert Big House, or ceremonial house, which is the largest traditional native structure ever built in the Pacific Northwest.

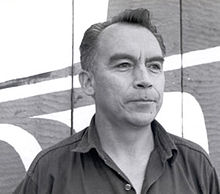

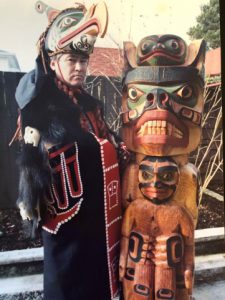

Richard Hunt is another of Henry Hunt's children. Born in 1951 in Alert Bay, Richard began carving at the age of 13, apprenticing under his father at the Royal British Columbia Museum. In 1974, Richard became the chief carver at Thunderbird Park after his brother Tony Hunt, Sr. stepped down. He remained in the carving program at Thunderbird Park for nearly twelve years. In 1986, Richard launched a new career as a freelance Aboriginal artist. His native name, Gwelayowelagyalis, translated to "a man that travels and wherever he goes, he potlatches" is appropriate as through his art, his speaking, and his dnacing, Richard has given much to the world.

The Leepa-Rattner Museum of Art is proud to present a work of art produced by Richard Hunt, a totem pole carved in the 1980s. This polychromed and carved wooden pole, measuring in at 71 inches high is on loan to LRMA from the St. Petersburg College Foundation who reeived it as a gift from the Estate of Rita Hayes and Robert Russek Scott. As typical in totems, the figure on top is the most important and often represents the family crest. Here the totem illustrates: Frog (rebirth, fortune, medicine, peace); Bear (strength, courage, guardian); Human (transformation, specific person).