Women's History Month - 2021

Women’s History Month began as a national celebration in 1981 with the passing of Pub. L. 97-28 by Congress which authorized and requested the President to proclaim the week beginning March 7, 1982 as "Women's History Week". Over the next five years, Congress continued to pass joint resolutions designating a week in March as "Women's History Week". It was in 1987 that the National Women's History Project petitioned Congress to pass Pub. L. 100-9. This act designated the month of March as "Women's History Month". Since 1995, presidents have issued annual proclamations designing the month of March as "Women's History Month". The goal of this month-long celebration is to recognize the contributions that women have made to the United States and the world. Now more than ever, these celebrations also include a call to action for gender parity.

Here at the Leepa-Rattner Museum of Art, we're celebrating Women's History Month 2021 by highlighting some of the incredible Native American women from the 19th century to today in conjunction with the current exhibitions on view: Jared Ragland + Cary Norton: Where You Come From Is Gone, Leonard Baskin: Native American Portraits, and About Face: Celebrating Diversity. The women chosen below reflect the incredible passion, talent, and perseverance of all women.

Sakakawea

Sakakawea, a.k.a. Sacagawea, was born in 1788 into the Agaidika (Salmon Eater) tribe known as the Lemhi Shoshone near present-day Salmon, Idaho. At around the age of 12, she and several other girls from the tribe were taken captive by a group of Hidatsa in a raid. After a year in captivity with the Hidatsa, at the age of 13, Sakakawea was sold into a non-consensual marriage to a Quebecois trapper named Toussaint Charbonneau

Sakakawea, a.k.a. Sacagawea, was born in 1788 into the Agaidika (Salmon Eater) tribe known as the Lemhi Shoshone near present-day Salmon, Idaho. At around the age of 12, she and several other girls from the tribe were taken captive by a group of Hidatsa in a raid. After a year in captivity with the Hidatsa, at the age of 13, Sakakawea was sold into a non-consensual marriage to a Quebecois trapper named Toussaint Charbonneau

In 1805, at the age of 17, Sakakawea and her husband were hired by The Corps of Discovery to aid Captains Meriwether Lewis and William Clark to guide their exploratory party up the Missouri River. Having given birth just two months prior to their departure to her son Jean Baptiste, the presence of Sakakawea and her child were an indisputable asset to Lewis and Clark – war parties did not take along women and children, and as such, the group of explorers was not seen as a threat by the tribes they encountered.

Sakakawea assisted Lewis and Clark in many other ways: when a boat capsized, she was the one who saved navigational tools, supplies, and important papers. She was able to locate edible and medicinal roots, plants and berries for the group. Her memory of landmarks proved invaluable for the explorers, and her knowledge of the Indigenous languages made her an expert translator for the group.

After the expedition, Sakakawea and her husband returned to the Hidatsa-Mandan villages. Though Lewis and Clark paid for her work, Sakakawea did not receive any of her pay. Her husband kept the $500 and 320 acres to himself. Clark acknowledged the unfairness of this in an 1806 letter to Charbonneau and extended to Sakakawea and her husband his friendship and offers to educate their child Jean Baptiste. He wrote,

You have been a long time with me and conducted your Self in Such a manner as to gain my friendship, your woman who accompanied you that long dangerous and fatigueing rout to the Pacific Ocian and back diserved a greater reward for her attention and services on that rout than we had in our power to give her at the Mandans. As to your little Son (my boy Pomp) you well know my fondness of him and my anxiety to take him and raise him as my own child.… If you are desposed to accept either of my offers to you and will bring down you Son your famn [femme, woman] Janey had best come along with you to take care of the boy untill I get him.… Wishing you and your family great success & with anxious expectations of seeing my little danceing boy Baptiest I shall remain your Friend, William Clark. [sic]

Lozen and Dahteste

Lozen was born around 1840 in the Chihennes or Warm Springs Band of Chiricahua Apaches. Her brother was Chief Victoria (Bi-duyé).

Lozen was born around 1840 in the Chihennes or Warm Springs Band of Chiricahua Apaches. Her brother was Chief Victoria (Bi-duyé).

Although she was well known among the Apache, accounts of her role in the Apache wars of the 1870s and 1880s were not published until the late 20th century. These show that she was a leading figure in the final episodes of Native American armed resistance to the invasion of their lands.

Throughout many Native American groups, there is a belief in the “two-spirited” individual. Two-spirit is a name for people in Indigenous culture who carry the duality between the sacred feminine and sacred masculine within them, though definitions vary per Indigenous nation and person. Although this was not formally documented amongst the Apache, Lozen often eschewed the traditional roles of Apache women, favoring the art of war, never marrying, and was often described as being more masculine than other men in her tribe. She was a leader in her community before she became a medicine woman and a warrior for her tribe.

During a vigil at the time of her puberty feast, she received the power to heal wounds and locate the enemy. She subsequently studied with older shamans and undertook additional vision quests. Her skills in riding, fighting, shooting, roping, and horse stealing were legendary and favorably compared to exploits of men. In camp, she continued to do women’s chores, but also tended horses. She was called “Dextrous Horse Thief” and “Warrior Woman.” As a fighter, she was as formidable as Victorio, who once said, “Lozen is as my right hand. Strong as a man, braver than most, and cunning in strategy, Lozen is a shield to her people”(Ball, In the Days of Victorio, p. 15).

After her brother was killed in battle, Lozen banded with Goyatla, a.k.a. Geronimo, to exact revenge on the colonizers who had stolen her brother and the land from her people. It was while she traveled with Goyatla in southern New Mexico that she met Dahteste.

Dahteste herself was a Chokonen Apache warrior. In her youth she rode with Cochise’s band in southeastern Arizona. Despite being married with children, Dahteste took part in raiding parties with her first husband Ahnandia. Some years later, she joined Goyatla’s band and rode alongside both him and Lozen. Dahteste was fluent in English and acted often as a translator for the bands she traveled with.

After helping Geronimo escape from detainment at the San Carlos Reservation in 1885, she, with help from Lozen, began negotiating treaties of peace for their people. One such treaty stated that after a two-year, voluntary imprisonment, the Apaches would have their freedom. American leaders at the time dismissed this treaty, and despite having been a mediator and scout for the U.S. Calvary, her loyalty to both her people and the U.S. Army did not prevent her eventual arrest alongside Goyatła and Lozen in 1886.

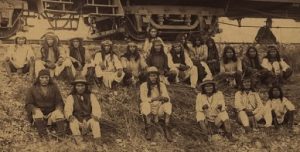

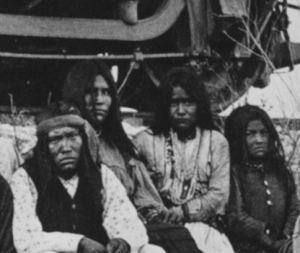

Apache accounts describe Lozen and Dahteste as regular companions at this time. In the 1930s, Apache informants told anthropologist Morris Opler about two unnamed women who lived together during imprisonment and had sexual relations—undoubtedly Lozen and Dahteste.The only photo that survives of Dahteste and Lozen was taken after they had been captured, before they were separated. In the photograph, they are seated close together, along with Goyatla and other warriors in front of the trains that would soon take them, via cattle cars, to prison camps in Florida and Alabama.

Having eluded capture for over a decade, Lozen died, aged 50, as a prisoner of war in Mobile, Alabama from tuberculosis. Dahteste however, was held in St. Augustine, Florida for eight years in an internment camp. She survived pneumonia and tuberculosis there before being shipped to Fort Sill, Oklahoma. There she remained a prisoner for another 19 years before being granted her freedom and “permission” to join the Mescalero Apache in New Mexico. There she refused to speak English ear again and lived out the rest of her life. Bbiographer Eve Ball who interviewed Dahteste before her death, wrote that, “Dahteste to the end of her life mourned Lozen.” Today, we should remember these two women as being devoted to their people, their land, their freedom, and each other.

Zitkála-Šá

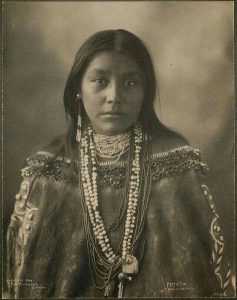

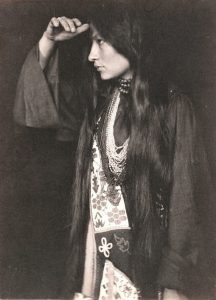

Zitkála-Šá was a Yankton Dakota writer, editor, translator, musician, educator, and political activist for women and Native civil rights. While growing up, she divided her time between South Dakota’s Yankton Reservation and a boarding school for Indian children in Wabash, Indiana. It was at the boarding school, a tool by which the United States government attempted to erase Native heritage and culture, that Zitkála-Šá learned to read, write, and play the violin. In 1895 she graduated from the school and upon receiving her diploma, delivered the first of her many speeches on women’s inequality.

Zitkála-Šá was a Yankton Dakota writer, editor, translator, musician, educator, and political activist for women and Native civil rights. While growing up, she divided her time between South Dakota’s Yankton Reservation and a boarding school for Indian children in Wabash, Indiana. It was at the boarding school, a tool by which the United States government attempted to erase Native heritage and culture, that Zitkála-Šá learned to read, write, and play the violin. In 1895 she graduated from the school and upon receiving her diploma, delivered the first of her many speeches on women’s inequality.

Forging ahead, Zitkála-Šá received a scholarship to attend Earlham College in Richmond, Indiana, despite the fact that higher education for women was quite limited at the time. It was while studying there that she began her efforts to record Native American oral histories and translate the into English.

In 1902 she married Captain Raymond Bonnin, who was Yankton Sioux. Over the course of the next decade, Zitkála-Šá joined the Society of American Indians. Through her writings, she called for the preservation of the Native way of life and lobbied for Native Americans’ right to full American citizenship. In 1916, Zitkála-Šá and her husband moved to Washington, D.C. where she lectured on the cultural and tribal identity of Native Americans. She promoted a pan-Indian movement which aimed to unite all of America’s tribes in the cause of lobbying the U.S. government for citizenship rights. This ultimately led to the passage of the 1924 Indian Citizenship Act.

In 1926, Zitkála-Šá and her husband co-founded the National Council of American Indians, which continued to lobby for Native women’s suffrage rights. She served as the council’s president, public speaker, and major fundraiser until her death in 1938. In 1997, she was designated a Women’s History Month Honoree by the National Women’s History Project, and her legacy lives on today as one of the most influential Native American activists of the 20th century. Through her activism, Zitkála-Šá was able to make crucial changes to education, health care, and legal standing for Native American people and the preservation of Indigenous culture.

In 1926, Zitkála-Šá and her husband co-founded the National Council of American Indians, which continued to lobby for Native women’s suffrage rights. She served as the council’s president, public speaker, and major fundraiser until her death in 1938. In 1997, she was designated a Women’s History Month Honoree by the National Women’s History Project, and her legacy lives on today as one of the most influential Native American activists of the 20th century. Through her activism, Zitkála-Šá was able to make crucial changes to education, health care, and legal standing for Native American people and the preservation of Indigenous culture.